Bays of Dismay 2: D’Entrecasteaux Channel: Mickeys Bay (Great Taylor Bay)

BAY OF DISMAY 2

Once, in Alaska, poking about a waterway, we watched the first salmon return to breed. Their life cycle begins in the gravels of the home river where they are born. They leave it for the ocean but return to it to breed, recognizing it by its scent, along with other cues. The icy chill, the glacier, the clear stream and the salmon (now more ruby than silver) made for a moment of mystery and magnificence.

Those were sockeye salmon, but the Atlantic salmon farmed in Tasmania are not native here and these days there’s a lot of conversation – protest even – about the environmental impact fish farms are having. Resistance has been growing against their planned expansion in Tasmanian waters.

That luscious pink steak on a plate had grown extremely popular because it was regarded as a gourmet choice – healthy, sophisticated and quick to prepare. Ethical, even, with many believing that farmed fish take pressure off wild piscean populations. That’s turned out not to be true (although the ratio of wild stock in feed has diminished somewhat) and farmed salmon are not naturally pink fleshed, people have learned. It has also become more commonly known that controlling disease outbreaks in pens is a difficult management issue that sometimes involves the use of anti-biotics. Seals still die seeking salmon in the farms, although not as many as in the early days but search through the relevant agency’s right to information index indicates that relocations are still frequent. Hundreds of birds get entangled each year. It’s a young industry leveraging off being clean and green but environmental sustainability, especially in a time of climate change, is tightly constrained by environmental factors, such as warming oceans, and the perception many have is that they have betrayed public trust about their practices and could do a whole lot better. They say they’re trying and the three companies have chosen different ways of improving but the chorus is growing that fish farms do not belong in bays.

Sailing, the sight of pens in an otherwise beautiful location that would normally elevate one’s spirits has quite the opposite effect. They can be noisy, spoiling the serenity of otherwise quiet anchorages. There is a particular one that is always in the way when I want to tack. Debris can mess with propellers and cause injury and it’s not always apparent when there’s a tow underway. These are situations that can be dangerous. Fatal, even. On the other hand, they have brought much needed employment to Tasmania and generate considerable wealth for the state.

***

GREAT TAYLOR BAY

Great Taylor Bay is off South Bruny Island with Partridge Island protecting its north western entrance. There’s a popular anchorage off the island. We ducked in here to escape bad weather on our way down to Recherche Bay this last summer. South Bruny National Park is at the southern end. Jetty Beach, also down south, is probably the best known beach in this bay because of easy public access. Too easy maybe. When we were last here there were five vehicles spread along the beach and this in a national park. There are anchorages along Great Taylor Bay’s eastern flank at North Tinpot Bay, Tinpot Bay and Mickeys Bay.

Great Taylor Bay, like all the D’Entrecasteaux bays, is really beautiful – the moody water, the forests, beaches and the islands. It can feel wild and remote, approaching by boat, so long as you ignore the dark farm with its caged salmon secured near the entrance of the bay. Tassal has a 30 year lease here and there were seven or eight pens that I counted as we sailed passed making for Mickeys Bay.

MICKEYS BAY

Mickeys Bay, an embayment off Great Taylor, can’t be accessed by road. It’s surrounded by hills and forest, has a lovely serenity and offered good protection from the prevailing wind one day in February (2017) when we decided to anchor here. It has a fairly narrow entrance, guarded on each side by the other two islands in the Partridge Island Group – Seagull Rock, a tiny islet, and Curlew Island, somewhat bigger. There are a few properties around the edge of the bay, although they are set well back and are relatively unobtrusive.

There was a yacht already there and by the time the stars were out we were nine overnight.

The next day, once all but two other yachts had sailed away, the geo decided to do a spot of fishing from the tender. Flathead were plentiful in 2005 when the Lady Nelson overnighted here, I later discovered, and he was hoping to catch us dinner. Another couple had also decided to put fish on the menu. They’d spread a gill net between Curlew Island and the shore. Just putting it out there, but in my humble opinion these should have been banned decades ago. Along with a fish for the plate, there’s the by-catch factor that can include seabirds of which Curlew Island has a few.

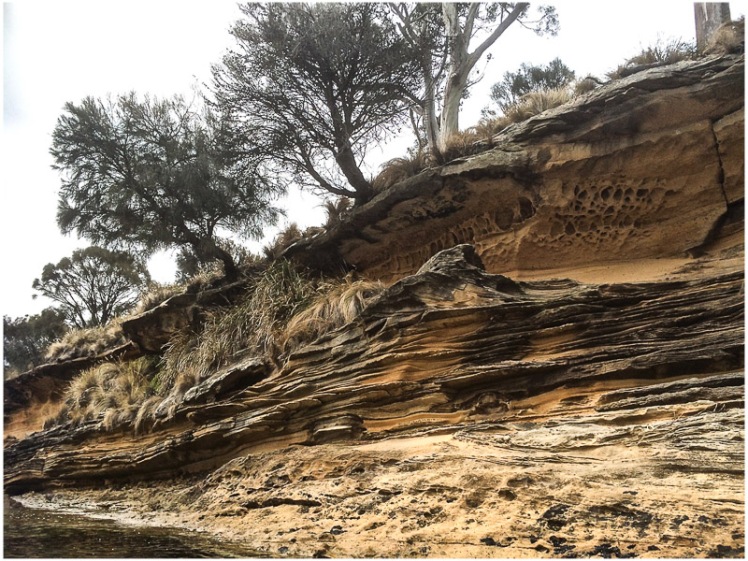

I decided to circumnavigate Mickeys Bay from Seagull Rock around to Curlew Island. It was sunny, the water was still and clear. There’d been a full moon the night before and the tide was way out. The conditions were perfect.

I kayaked over to Seagull Rock and began to work my way back along the bay, kayaking over and beside a fringe of seaweed, mostly those beautiful strappy canopy forming brown macroalgae, like kelp. I was expecting to lose myself to the beauty, but beauty wasn’t what I got. They lacked the variety and robustness of the ones I’d seen in the Tinderbox Marine Reserve. That’s not surprising in a quiet bay like this one, but their vivacity was frequently lost within the dirty brown miasma of a brown filamentous species, similar if not the same as one I recollected seeing at Baretta. It looked to have attached itself into the thallus of the seaweed like a parasite and seemed to be successfully suffocating everything it encountered. On the few occasions that I found something still vibrantly alive, the brown miasma was right up beside it, rocking and rolling with the movement of the water, just waiting to pounce. Or so it seemed to me, a novice in the world of seaweeds.

I was doodling along but often I stopped and floated, trying to figure out what I was seeing. I wondered if my perception was skewered somehow, if maybe Tasmania just happened to have some dead ugly reefs. If maybe a species as dominant as this ugly miasma could be normal. But what kept coming vividly to mind was my favourite Eastern Cape (RSA) river, the Kwelera, and how over the course of one summer we watched grey water from an ablution block turn a happy rocky shore into a soapy, slimy one where nothing grew.

Each time I reached one of the beaches around the bay I walked, collecting plastic and other litter. I was disappointed at just how much of it there was. Some was fish farm debris, the lines entangled in old washed up branches or caught up on the wrackline, which, I noticed, on the longest, sandiest beach, had spilled over the low bank, with plastic sometimes caught up in a tussock or lying in a thin line on the grass.

The day I had thought would be wonderfully spent on the water was turning out to be a dispiriting experience but I expected that on the deeper, eastern side of the bay, in shadow cast by the forest that afternoon, the seaweed would be healthier.

It wasn’t.

I walked this pebbled northern shore. I floated above the seaweed. It seemed to me it was an opportunistic seaweed invading the space where others should grow.

In the distance I could hear the rumble which we’d earlier concluded must be coming from the fish farm. I thought about its possible impact – the faeces, the unswallowed food, the way the debris accumulates beneath the pens before it is picked up by the currents and tide and I wondered if anyone knew how those currents might move around Great Taylor Bay. It seemed to me entirely feasible that if fish farm debris was washing into Mickeys Bay, then nutrients were making it in here too and given its shape they might be having a hard time flushing back out.

Observing this bay of dismay I wondered if what I was seeing was the result of a seasonal trigger, climate change, the impact of habitation or the passing parade of yachts that might have poor waste management strategies.

Or all of these things combined.

I hadn’t noticed anything amiss when I’d first paddled from the yacht to the shore. The water was clear. I’d seen ripple marks in the sand and down beneath me what I took to be seagrass standing upright, all at a distance from each other. But later, when I studied the photos I had taken, I noticed that in the little hollows small clouds of that miasmic seaweed seemed to be resting like brown cotton wool. Studying my photos later I couldn’t decide if the seagrass was healthy or not. Searching the web I struggled to identify this filamentous alga.

CURLEW ISLAND: BIRDS AT RISK

Curlew Island is 0.415 hectares of non-allocated Crown Land, and at least in 2001 was home to Pacific and Kelp Gulls, Sooty and Pied Oystercatchers as well as Caspian Terns who have (and possibly still do) use it as a breeding site, along with Black-faced Cormorants, Little Black Cormorants, Great Cormorants and Silver Gulls (Brothers et al, 2001).

On the point near Curlew Island there were a whole lot of pipes and what looked like a fish farm pen in the process of being built. The land just there had a most unpleasant vibe because of the mess lying about in what had seemed at first glance to be a lovely wooded area. I looked at that island and noticed some birds. I considered that net. I thought about that fish farm, about 5 km away, and how, when you sail by, you often see birds hanging about the pens. No place for a net, I thought. And I didn’t like the idea that birds from Curlew Island might get entangled in fish farm netting.

Until I’d noticed the mute trouble the bay is in it had seemed stunning. I’d paddled around it, drifted, communed with it. I’d walked it. I’d seen two tiny groups of minuscule silver fish (less than a dozen in each) and I’d seen a ray.

‘Good paddle?’ the geo asked when I got back. I told him about the trouble I’d seen.

‘How was the fishing?’

‘Two little flathead too small to eat.’

***

But now, months later, I wonder if I was entirely wrong about what I saw.

The more I read the more it seemed that studied opportunistic species associated with fish farms are green, like Ulva and Chaetomorpha and they weren’t on my radar as I kayaked. On the web I finally located a look alike species to the ‘miasma’ called Ectocarpus, found in New Zealand and elsewhere in Australia. There are two varieties in Tasmania (one also found at Eaglehawk Neck) and they are migrants from the UK that have grown resistant to anti-foul and heavy metals like copper. This species hasn’t been studied much from what I can see and although to me, a rank amateur, it looks opportunistic, I haven’t noticed it linked to fish farms.

Which begs the question – why is it so abundant in this bay? If my identification is correct, then is it thriving on heavy metal contamination here?

Tassal’s baseline environmental monitoring program doesn’t cover Mickeys Bay but they do have a monitoring spot in the middle of Great Taylor Bay, M8, that has indicated higher than average chlorophyl readings and Oh’s thesis also notes increases in opportunistic * green algal species in Great Taylor Bay. She monitored just outside Mickeys Bay.

I would really like to see Tassal include Mickeys Bay in its broadscale environmental monitoring program (BEMP) because both boats and fish farms use anti foul, although fish farms are apparently trying to phase it out. Tassal is farming a waterway they do not own, a waterway in which the public, marine mammals, birds and other species have a vested interest and it would be a way of returning the favour that both the community and the environment are extending to them were they to increase their monitoring stations.

In 2014 the Aquaculture Stewardship Council auditing team identified areas where Tassal could do better. Principle 2 (Conserve natural habitat, local biodiversity and ecosystem function) related to feed testing and making lethal incidents publically available within 30 days. Principle 3 was about protecting the health and genetic integrity of wild populations through the development of an area based management plan (my italics) and Principle 4 (Using resources in an environmentally efficient and responsible manner) related to the feed ingredients used at the farming sites. Tassal also has to abide by Principle 5 (Manage disease and parasites in an environmentally responsible manner) and was also advised it could do better in relation to Principle 7 (Be a good neighbour and conscientious citizen).

Tassal holds Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) salmon certificates for the Tin Pot Point and Partridge Island farm sites, according to WWF’s the Aquatic Stewardship Council scheme, but there is concern about bias in this regard.

Changes in the Channel have been noted by many, including abalone divers and recreational fishers. The fact is, that since the first species let go their grip on the hulls of the boats of the first explorers from Europe, the D’Entrecasteaux has been disrupted by a multiplicity of different activities, visitors and the like. It’s just been growing ever more intense, to the point where it’s health is of growing public concern.

The more I read the more interested I became in fish farms, concluding that they do not belong in bays at all. But I also began to consider the impact of my own sailing on the environment and the things I could personally do to reduce this. If there are heavy metals in Mickeys Bay then less damaging anti-foul needs to be considered.

- See Macleod (2016) noted below.

Some Reading:

Brothers, Nigel (2001). “Tasmania’s offshore islands : seabirds and other natural features”. Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart

Tasmania’s salmon trade casts deadly net. Australian, 22 June 2013

Dangerous dinners. Is salmon farming ruining Tasmania The Australian 22 Dec 2016

Flora SA. (database) Ectocarpus fasciculatus

D’Entrecsteaux and Huon Collaboration. (2016). D’Entrecasteaux and Huon report card 2015 NRM South, Hobart. (see pg 14 for deaths and entanglements).

Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (2016) Understanding broad scale impacts of salmonid farming on rocky reef communities FRDC Project No 2014/042 2016

Report for Tassal Operations Pty Ltd: Huon Region – MF 185 Tin Pot Point and MF 203 Partridge Island : Full Assessment Against Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) Salmon Standard V1.0 Tassal Operations Pty Ltd

This report notes: ‘Opportunistic species should not always be considered bad, they are a natural part of an the functional ecology of an estuary and serve a very useful role in “mopping up” excess nutrients. Consequently their presence can actually help ameliorate/ remediate the effects of nutrient fertilization. It is when they actually alter the structure and function of communities that they should be considered undesirable.’