D’Entrecasteaux Channel: North West Bay by kayak

What my kayak and I discovered in Ranggoeradde [North West Bay]

The Tortoise and the Elephant

And so I left vibrant Tinderbox Marine Reserve behind me and turned into Ranggoeradde, better known as North West Bay. Calling it by a name so redolent in history restores something of its original character, despite the fact that it has been stripped of its myths and stories and the people who told them aren’t really recognised anymore.

A lot may have been lost in translation. It’s easy to withhold, mislead, confuse or misunderstand when it comes to words and their meanings, particularly when the relationship between the teller and the person with the quill is untrusting, or uncertain at best. Ranggoeradde may not have been properly translated at all.

It’s a low energy embayment of about 2,000 ha. and it now lay spread out before me. It’s eastern shore is also the western shore of the Tinderbox Peninsula and it’s easy to forget this as you wander about this area. There’s a long winding road that feels its way down that particular edge of the bay, past a number of Howden houses set in big blocks of land, a couple of small bays (somewhat muddy) and a bus shelter that doubles as a local book exchange or perhaps a community library. It’s a good road to cycle but it’s still on my ‘to do’ list. It’s a good area to walk too, and on this eastern side there are three spots of interest: Wingara, Stinkpot Bay and the Peter Murrell Reserve, and I was heading to Wingara to catch up with the patient geo.

The further I went into the bay, the more I noticed that diversity beneath my kayak was diminishing, and I realised that this bay is like a tortoise trying to support an elephant on its stoic little back. It carries the suburb of Howden, the country towns of Margate, Electrona and Snug, as well as Conningham, where shacks along a short series of sandy beaches now make up something of a commuter suburb.

The North West River plummets down the southern slope of kunanyi (Mt Wellington) and when it happens to be dry its bed gleams with large, pale boulders and when it’s in flood it’s strength is so awesome your breath catches. It enters Ranggoerrade, and so does the lovely Snug Rivulet, hugging its secrets to itself in a dreamy sort of way, a perfectly beautiful miniature estuary. They, along with various rivulets entering the bay, carry local litter, grey water, toxins and the like. That’s more than enough, but there’s a fish farm here that ups the nutrient load, a bit of light industry (pre-cast concrete and glazing), a seafood factory and a marina, moorings and a boat yard as well as a sewage works. (Jordan et al. 2002) as cited here.

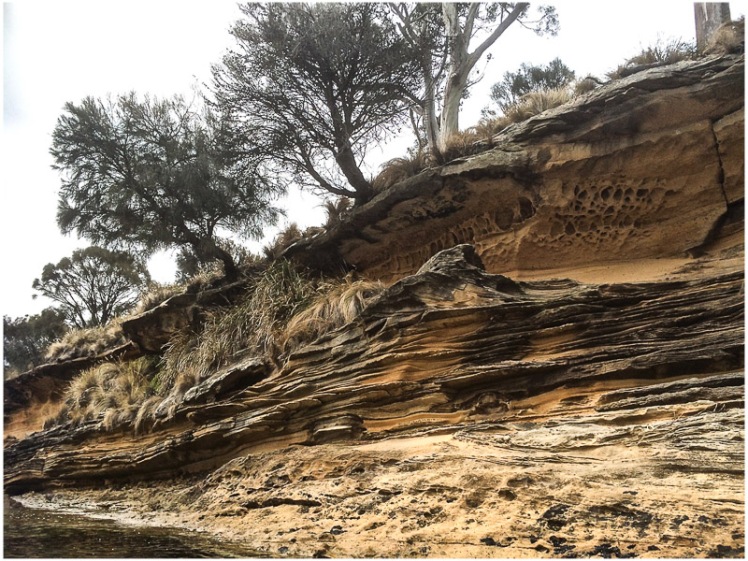

It wouldn’t take me long to reach Wingara, I figured, but then I saw the sandstone cliffs and my speed slackened off again. They were stunning and I got snap happy. Never high, they sloped downwards, eucalypts and grasslands above, and gave way to a cobbled shoreline.

Andrew Short (2006) doesn’t mention beaches on this side of the bay in his inventory of Tasmanian beaches, and I had flipped my strategy for exploring beaches. Instead of high tide, for the D’Entrecasteaux and kayaking I wanted high tides, expecting mostly muddy shores. That’s why, on this trip, I sometimes floated above beaches drowned by the tide and gazed at ancient ones laid down in the sandstone’s stratigraphy. I came to a cove with a private beach and tried that lifestyles on for size.

It was as I paddled along the shoreline beside the fish farm that I really noticed the decline in seagrasses and seaweed. From the fish farm and that first house on the shore, it became less interesting beneath the water but the cliffs were awesome. Sometimes I had to go out a little wider to avoid the ‘bommies’. Occasional the kayak scratched as I went over them in too shallow water. I was constantly lifting my rudder.

I negotiated the fish farm and the Wingara jetty, passing cormorants holding their wings out to dry. The geo was standing on the rocky platform staring at the cliffs. So far, it had been an absorbing paddle, but I thought how westerners accuse some of the cultures amongst whom they’ve settled their flagpoles of not planning for tomorrow. We haven’t necessarily recognised that actually, we are the ones that haven’t planned for tomorrow in the most significant of ways. We’ve used up ecosystems like their isn’t going to be one. We’re the destruction and destruction doesn’t give a damn. That’s why all around us there are tortoises balancing elephants.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A little more about this tortoise and that elephant:

The State of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel and the lower Huon Estuary report (Parsons, 2012) states the following about North WestBay:

- At risk from nutrient loading due to high terrestrial inputs of nutrients and reduced flushing times

- Experiences turbidity values far in excess of the upper national guideline value during high flows of the North WestBayRiver

- Dissolved oxygen (DO) levels in North WestBay are variable and have dipped as low as 58% saturation in bottom waters during summer, reflecting poor environmental health

- Occasional elevated values of contamination highlight the vulnerability of some beaches and other recreational sites to short‐term spikes in bacterial loads. Primary areas of concern in recent years include Margate and Snug

- Evidence of environmental legacy issues at the former heavy industrial site at Electrona, although measures have been implemented to mitigate impacts on the Channel

- Heavy metals are also elevated in sediments in deep, silty areas of North WestBay