Tasman Peninsula: Dark Deeds at Sloping Main

Tasman Peninsula and the beaches of Frederick Henry Bay: Sloping Main in Stinking Bay (T340)

A Fabulist Disappears

Once, in Africa, we met a charismatic man we thought might be a fabulist. Over drinks, as we watched wildlife grazing the plains from the comfort of a lodge, he told us mesmerising stories about his role in the Entebbe raid and other incredible boy’s own adventures in wild and dangerous places, where, risking his life time and again he escaped miraculously.

Mostly we were awed, but when one of us expressed scepticism he told us, ‘every few years I change my job and that way I change my life. That’s how I’ve done so much living’. And afterwards, asking each other, could any of it be true one of the locals said, ‘all these things – they all happened far away.’

I was reminded of the enjoyable time spent in the company of this man when I researched Sloping (aka Slopen) Main and discovered that one day a fabulist trailing many names but not much else, had arrived there and made himself comfortable in an old convict hut on a farm behind the beach.

Old Habitations

On Sloping Main Marsh, before the Port Arthur penitentiary was built to accommodate the convicts petty and otherwise off the streets of Britain, settlers built a farm. It was the 1820s and these weatherboard buildings are the oldest on the Tasman Peninsula. A short drive away there’s the Surgeon’s cottage (red brick) and a house associated with the semaphore system, but I walked this beach not thinking about history, and I walked in ignorance of a tale of secret liaisons, disappearance and assumed murder that happened here in the Saltwater – Slopen Main area of the peninsula back in the 1980s.

Walking Sloping Main

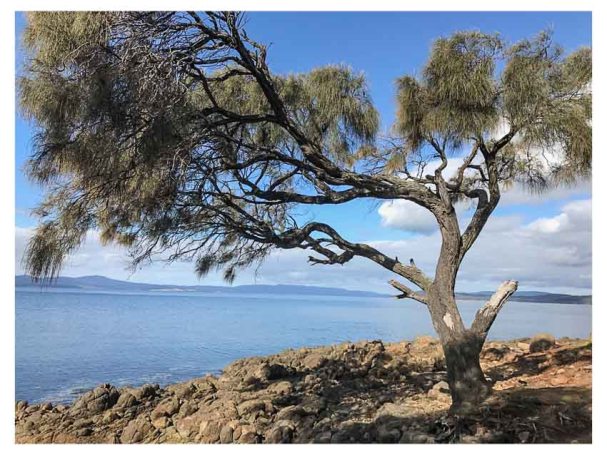

The beach is a 3.5 km long crescent that faces west with Cape Deslacs and Cremorne visible in the distance. It’s bounded by Black Jack Point below Gwandalan (southern end) and Lobster Point to the north, with Sloping Island just offshore in Stinking Bay.

It was raining over the mountain and the sky was dramatic with clouds, shafts of sunshine and drifts of rainfall. A bevy of clouds was being driven across Storm Bay by the South Westerly heading in our direction. Behind us Gwandalan, a small community of seaside cottages and shacks, perched on the lower edge of Mount Wilmot, just above the point. In front of us a stunning sweep of white sand purled off into the distance and behind the dunes on the forlorn and muddy flat, the land said nothing of dark events.

The wrack line lay along the base of the small incipient dune and was no more than a delicate wavering line of seaweed. Marram grass had taken hold, threatening the gradual gradient of a back dune. There were eucalypts poking out of the dunes, both the living and the dead and there were gutting tables every so often and sometimes a bench. It’s a low energy beach but the waves that day were hectic and the tide was low, the white sand lined with cusps.

We passed a dead cormorant and two dead fish. We passed kelp glistening on the swash. We walked through a light shower and the temperature dropped – it was summer but snow was forecast. After a bit more than an hour we reached the Cardwell Cliffs and stood below the headland contemplating the start of Lime Bay National Park above our heads. A quick scramble up and we’d have found a walking track. Whalebone Beach is on the other side.

Because of the wind we hoped to find a track behind the dunes, which had widened here, but there was nothing. We found ourselves standing on the bed of a dry rivulet, a crust of white over the mud beneath. Burdens Marsh, partly drained, was dry but there was a fence and then farmland and so we turned back. Twelve oyster catchers walked ahead of us, flying occasionally to maintain a safe space. A seagull foraged for sand mussels. High on the cliffs the small community of Gandwanan looked tiny in the vast landscape of sea, islands, peninsulas and distant shores. That day, because of the moody sea, the landscape seemed gothic and ominous. Even the names seemed gothic. I did not yet know about The Disappearance.

Man of Mystery

The fabulist, a man of no fixed name or address, was invited to stay in that simple hut by the farming couple who owned the land. He and his wife knew him as Reuben. Other friends concurrently knew him by different names entirely. Later, piecing together the story, the coroner concluded that he was Tony Zachary Harras, sometimes Harris, born in the UK in 1934. Some of his aliases were Judah Zachariah Reuben Wolfe Mattathyahu, Karl Wolfe, Carl Wolf, Reuben Wolfe, Zac Mattathyahu, Reuben Mattathyahu, Carl Mattathyahu and also Karl Mattathyahu.

Beaches acquire different names through no actions of their own and Sloping Main and the island just offshore also have a slippery identity. I couldn’t find their Aboriginal names, but the explorer, D’Entrecasteaux, christened it Frederic Henri / St Aigen when he sailed by in 1792, according to Tasmanian Nomenclature. In 1798 Flinders, circumnavigating Van Diemen’s Land in the Norfolk, called it Sloping Island and that’s officially what it is today, but it’s just as commonly called Slopen and occasionally Storring. The Slopen might come from a whaling captain, a farmer or a lazy corruption. The beach and the island share that same identity. (Here’s a bit more about that history.)

Unlike the beach and the island the fabulist actively chose a whole series of names. Why does a man need that many names unless he has profound identity issues, fears for his life or is up to no good? At any rate, I’m calling him Tony – just because it’s authentic when so little else about this story seems to be.

He began his working life in primary industry and moved on to the British Armed Forces before arriving in Australia at about the age of 24. The period he spent in the forces seems to have influenced him quite profoundly. Regardless, he was in Australia from 1958 to 1960, then travelled to New Zealand before returning to the UK. He changed his name to Tony Zackary Harras but he could not settle. He was soon back in Australia and then he was marrying in the UK. A son was born. On the birth certificate Tony is Zachary Anthony Harras, vermin controller.

In 1971/1972 he was working as a gardener at the Botanical Gardens in Adelaide and then threw that in to become a bushman near Maydena, Tasmania. His marriage was over and he told friends he’d spent time in Israel but in 2014 when the cold case into his disappearance was reopened, the coroner expressed scepticism about that.

At first, in Tasmania, he called himself Judah Zachariah Reuben Wolfe Mattathyahu but he referred to himself by random versions of that name so that various friends knew him by his pseudynyms concurrently.

This aura of mystery was enhanced by the incredible stories he told about himself. He put it about that after getting interested in Judaism he’d fought for Israel in the Six Day War. He said his wife and his two children died in a war but when and in which war remained vague as does that family. He told friends he’d gone to Africa with seven others to destabilise a government and was the only one that got out alive. He’d followed through on orders to kill seven men and then he’d escaped by chopper. He said he was mixed up in the Entebbe air raid, that the only person shot was his cousin but when that was investigated no proof was found. He also said he’d been a Nazi hunter. Assassin, mercenary… imagination or fact? These were events that happened far away and could not be verified, not even by the coroner.

Fact: He was logging on a property on the Tasman Peninsula, at Slopen Main Beach and at the invitation of John and Anne Hull, the owners, who knew him as Reuben, he moved into a little convict built building on their land. Anne, on this farm, that at times must have felt remote, must have fallen for the stories. Soon she and Rueben were deep into an affair, her family oblivious.

After the fabulist disappeared and the police came calling, she said there’d never been an affair, but this story didn’t hold up in court. It emerged that he’d phone and say he needed his shirt washed. This was the code they used. She’d dress up, at his request, in her black coat and boots and go over to the little convict building. His shirt needed washing often; sometimes three times a day. There was passion unfolding in that building and Tony, aka Rueben Mattathyahu aka whoever didn’t exactly keep quiet about it.

A friend in Hobart let him have the use of a room in the same building as his shop, a well known shop at the time, that sold outdoor gear. It became the scene of secret trysts. He showed friends photographs, explicit ones, of what they got up to in that room and so the affair was impossible for Anne to deny. Faced with proof and under further questioning her story changed. The relationship was nothing much, they seldom met, she had no time.

All this took place in the early 80’s. John Hull said he only found out about it when police arrived at the property in 2012 investigating this old, cold case but the coroner found that at the very least he knew in March 1984 when detectives showed him photographs of Anne and Rueben in the Hobart room. What had happened to Tony, they wanted to know. The police quizzed Anne too. She said John had been fishing up at the lakes the weekend Tony disappeared and she said that when she’d finally told John about the affair and offered to leave, they never spoke of it again. John, in 1984, declared he’d been at the lakes shooting, but at the coronial enquiry in 2014 he said he was in the killing shed slaughtering sheep after dark when Tony’s friend arrived to find out where the fabulist was. (The coroner didn’t believe he was in either of these places. The killing shed seems to me to be an ironic place to be at night shortly after a murder.)

The Hulls agreed that in the final weeks before the fabulist went missing he wanted to be alone. His employer at the time described him as “fearful” and “agitated”, another friend said that he was looking for other work, anxious to leave Sloping Main. Another said he thought he’d received a call from Tony, possibly after the Saturday in November that he was supposed to have gone missing. The coroner was sceptical that the date he gave was correct.

When the Hull’s son Alan was interviewed about those final weeks and that eventful night, he told the coroner he’d seen a terrible altercation and that he had “a sneaky suspicion” that ‘there was only one other time I seen him after that’.

He said his father had rung him up and said not to come home because Rueben was ‘behaving really badly, he’s about to go’ but Alan said, ‘I’m not real good at doing as I’m told. So I toddles home.’

That night, he said, he didn’t drive in as usual but parked in the bush and as he walked along the fence line where he could stay hidden he saw a ‘flash looking car’ he didn’t recognise and a rowdy fight taking place with ‘a bit of noise and clonking and banging you could hear and squealing…’ and these men he didn’t recognise had Tony by the feet as they came out the door. The fight went on, he said, but finally the fabulist got the upper hand and sent the men packing in their car.

That story, said the coroner, was untruthful and inconsistent because he could not adequately explain why he’d not called the police at the time, even though there was a phone at the main residence. Neither did he mention this to the police when they were investigating in 1984. In fact, the Hulls never did tell anyone Rueben had disappeared. It was March 1984, four months after he’d disappeared, before the friend involved that night told the police that his itinerant friend had vanished. That’s a long and puzzling gap. Long enough for any trail to grow cold.

Anne said in 2012 that the police interrogation she’d endured in 1984 was so traumatising it still gave her nightmares. Her memory was vague and inconsistent about the facts though. She’d said her husband was away deer hunting but when interviewed the next day he said he was away fishing at the lakes. (Although actually, up at the lakes, you can do a bit of both if you are so inclined, but John was pretty clear he’d only ever gone fishing there twice before).

Anne said Tony (only she called him Reuben) often left the property, mostly for employment purposes and at times up to three or four months. ‘During these times he was away.,’ she said, ‘I would have a forwarding address to which I wrote to but Reuben never replied. The last time I saw Reuben was with John at Black Jack Hill gathering sheep. Reuben did not say where he was going when he left in November and I have no idea of his whereabouts. John, Rueben and myself parted on good terms.’ (Years later, though, it emerged that he’d left a letter in the hut for them, asking them to ‘look after the things I love’ until he returned. It’s odd they didn’t tender this at the time. It’s also odd that if he feared John he would turn to him to look after his possessions.)

One Dark Night

A witness the coroner did find convincing was a friend who said Tony (only he knew him as Mattathyahu) had no car and relied on others for transport and had asked him the day before he disappeared to pass on a message to this friend’s cousin for a lift from Slopen Main to Hobart. The arrangement was for this cousin, who was Tony’s friend, to pick him up. The arrangement was that he’d return with him to Glen Huon. Tony would spend the night with him there and then the next day this same man would drive him into Hobart.

That’s some favour to ask for and some favour to give. The distance one way is 153 km or 2 hrs 18 minutes, excluding the trip into Hobart the next day, which would have been another 90 min return trip for the friend, and these distances and times are based on better road conditions than existed back then. It was a night time journey on a Saturday. That’s great generosity. The friend connected with the flat in Hobart where the liaisons took place, said Tony (only he knew him as Karl Wolfe) had told him he’d be coming by the next day to fetch some stuff and that he’d had ‘enough down there and had to get out’. But he never turned up and he never heard from him again.

The night he was expecting his lift out of Sloping Main to Glen Huon south of Hobart, the fabulist phoned the intermediary at 8.30 p.m. to confirm his lift was arriving. He was assured it would be arriving in about half an hour. This seems to have been Mattathyahu’s last contact with anyone, anywhere and it’s not clear from the coronial report where he made that phone call from, because he doesn’t seem to have had a phone at the hut.

The friend providing the lift (who the coroner also found to be a reliable witness) was the person who finally reported the November 1983 disappearance in March 1984. He’d visited Mattathyahu at the Sloping Main farm several times and he’d responded to the request for a lift, even though it involved this lengthy four hour plus return drive at night. He arrived at 9.30 pm to find lights on, doors open, and the two dogs in the yard. When the friend went into the empty hut the luggage was ready to go, so after a wait of about 15 mins, he went to the Hulls, a 10 minute drive away at Saltwater River.

He asked Anne if she’d seen Tony, and she said she hadn’t and so this friend, the reliable witness, went back to Mattathyahu’s dwelling. He said he checked his friend’s belongings – the sleeping bag, a couple of trunks, a toolbox, spade, axe and wooden club, the bags standing at the door.

He waited, but the fabulist did not arrive and so then he drove to the shop at Premaydena, a 20 minute drive away, passed Saltwater River again, to phone his cousin who’d given him the message, then returned to his friend’s place and waited again until midnight, and this I have to say seems incredibly kind hearted or downright concerned after that long drive from the Huon Valley, especially as he’d only got the message around 4 pm that afternoon, a Saturday and especially if it crossed his mind even just for a moment that his friend was simply standing him up or that there was some confusion.

At the 2014 cold case coronial enquiry, Anne also said that this friend came to their door but she described him as “scared stiff”. It was “darkish” and she told him she didn’t know where Reuben was. She didn’t know what date it was either but “there would have been family” at her place because ‘our place always seemed to be full of people and I can’t remember who they were. All I know is I’d look sometimes and there they’d be sitting around like little birds waiting to be fed.’

But she said when he was leaving she looked through a window and thought she saw Reuben in his car. So why, the coroner asked, was he asking for Reuben if Reuben was in the car (something the friend denied, as well as denying having company for the trip down, putting paid, as far as the coroner was concerned, to the notion of Alan Hull’s suggestion there’d been a violent altercation). And why was he so scared stiff? She said that would be because he’d seen Reuben, but she had no plausible response for why she hadn’t told the police this at the time, saying only that ‘he came and gone – he came and went as he so chose.’

Alan Hull said that despite his mother not remembering, he was at home on the evening of 12 November 1983 and overheard the conversation with the friend, who was a man he recognised. He, too, saw Reuben in the car and remembered thinking, ‘I wonder when I’ll see him again.’ But the coroner said this was a story designed to protect his parents, the main suspects.

The last witness was John Hull. In his 23 March 1984 statement he’d described how the fabulist began living on the property at Sloping Main, how he got to know him “reasonably well” and how they became friendly and saw each other twice a week.

He thought the last time he saw Tony was about Tuesday 8 November 1983 at his place about 5 pm. He’d seemed his normal self and had not said anything about leaving, although he knew he was looking for a job. Neither did he take much notice of the fact that he’d gone, but ‘now I am aware of the arrangements he made, I find it strange that he didn’t keep them, as he was a meticulous person.’

The night of the disappearance, when the friend had arrived at their house, he was in the killing sheds, slaughtering sheep, he told the coroner. Previously he’d said he was up at the lakes (Central Plateau). The coroner didn’t think he was in either of these locations and I can’t help wondering whether it is usual for farmers to slaughter their sheep at night.

He said on Sunday 13th he’d gone to Reuben’s camp to get his dogs and returned on several occasions to get tools and guns that belonged to him.

He also mentioned a telephone call he’d received ‘last Monday night 19 March 84’ from an acquaintance who’d seen the notice in the paper about Reuben and had told him he’d had a call from Tony around Christmas enquiring about a job. He said he’d asked Tony (only he called him Reuben) if he was out of money and he said he wasn’t.”

The coroner, after listening to the Hull’s stories found Anne to be ‘grossly exaggerating’ while too reticent about known facts. He said, ‘Those members of the Hull family who gave evidence were in my view at pains to present as a reason for Mattathyahu’s agitation and his intention to leave the idea in some way that his colourful past as a mercenary and Nazi hunter was catching up with him. The much more likely explanation in my view for any agitation and his making arrangements to leave, in something of a hurry, is that his affair with Anne Hull had been discovered by someone and he was anxious to get away from the locality.’

He found that Tony’s disappearance was homicide but could not establish the how and that ‘Mr Mattathyahu died on or about the 12 November 1983 at or near Slopen Main, Tasmania’.

Tony was a man clearly fascinated by war, not averse to killing ‘vermin’ or trees, or, according to the tales he told (truth or lies) killing people too. He is known to have had guns, spears and knives and a wooden club (Ford, 2019). It’s an open possibility, one can imagine, that he had enemies who no doubt knew him by some other name.

Out there, there is someone who either knew or knows the truth but isn’t telling.

For more information see the Historic Missing Persons Case and the Coronial Report. The Mercury newspaper also covered this story. Australian Broadcasting Commission. The disappearance of Judah Mattathyahu: Timeline of key events. Updated 23 Feb 2018. Url: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-10-02/judah-mattathyahu-timeline/6815882Ford, J. 2019. Unsolved Australia: Lost Boys, Gone Girls. Macmillan Publishers, Sydney