Derwent River: Blinking Billy to Hinsby Beach: Part 7: Reaching High School Point

The Name Confusion Never Ends

The eucalypt that had confused me as I approached Grange Beach a little earlier in the walk had done so because my next waypoint, already known to me, was another bleached eucalypt lying prone across pebbles and sand, supported on the tiptoes of its branches. But now, walking along south of Grange Beach I was still trying to clarify the coastline in my head. Where, really, did Grange begin and end? Why was what I was seeing not according with what I’d read in Short’s inventory?

I rounded a slight point and finally reached the eucalypt I’d encountered the previous Sunday, a day that had begun sluggishly because I’d been reading Cheryl Strange’s book Wild, about her long walk down the Pacific Crest Trail, well into into the early hours of the morning. It had made me itchy to get out and walk beaches again, especially as so much of my time had been spent on Samos, back in the water finally after a long time on the slip, but still needing new batteries and a new anchor. Down at the boat that Sunday, ready to do some work, the geo and I realised we could do nothing – the shipbuilder had one of our keys and we’d forgotten the other – and so, with just a short space in my day before heading off on a beekeeping course, I’d set off on my initial sortie into Taroona to identify beach access points.

I’d parked the car at the southern end of Flinders Esplanade and found a path that led down to the beach beside a double story house. This path followed the short, steep edge of a gully that was the home of a rivulet. At the bottom of the cliff a huge, bleached eucalypt tree stretched across the sand. On the other (southern side of the rivulet) another path ascended.

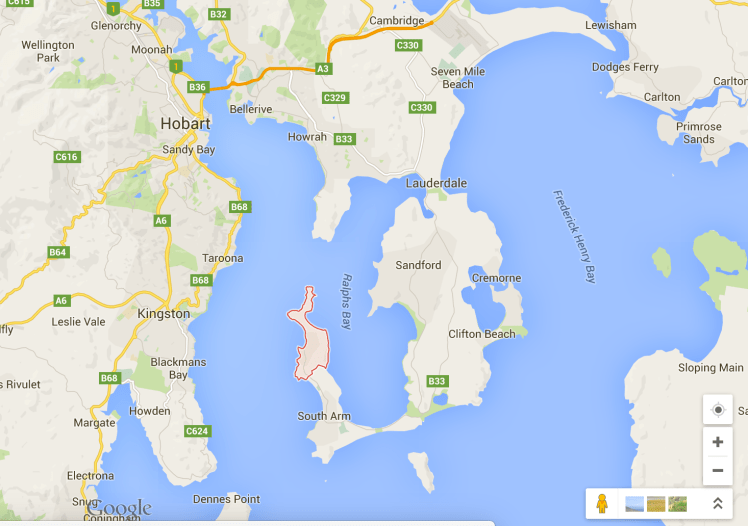

I thought initially that I was on the beach that Short calls T458 (aka Blinking Billy Beach 3 – yep, I know; I was very confused!) because he describes that as being a narrow reflective sand and rocky beach that extends along the base of 20-30 m high bluffs for 200m. Only this wasn’t that long – or then again, maybe on a different tide it was? I also thought that it might be T459 which he describes as extending south of the sloping 20m high Cartwright Point. When I read this I still thought that Cartwright Point was actually High School Point visible in the distance, so it didn’t make sense. (He says of T459 that it’s a narrow eroding beach, is backed by vegetated bluffs that rise to 20m in the south, that there are houses on top of them and steps at the northern end. Not knowing the shoreline to the north at all that Sunday, I decided for the time being that this was the one I was on, not thinking twice about the steps at Grange Beach.

Welcome to my geographically confused world!

I hadn’t had time on that Sunday visit to walk north of the eucalypt, otherwise I’d have realised then that in the absence of a firm nomenclature there are different ways of viewing the coastline. Short, it seems, has taken a larger coastal/geomorphological perspective and identified longer strips – the three Blinking Billy Beaches with the third extending to Mitah Crescent (I think), and Dixons extending south from Grange Avenue to Taroona High School and High School Point. It was only when I revisited on a summer spring tide that I saw that on this strip Grange, Karringal and Dixons really do become one.

That Sunday, I simply walked about on the shrunken sandy portion of the beach as far as I could go, which wasn’t far as the tide was quite high. It was indeed narrow here, and as you can see, there are a lot of cobbles and sand and a reef. I found a quite astonishing square rock pool carved into a huge boulder that looked at first like a boat and then like a plane. It’s at the southern end close to the geologically interesting cliff that barred my way further south on that particular tide.

So on my long walk I sauntered along knowing that at some point I’d see the bleached and fallen eucalypt below Karringal Court and when I did the somewhat longer beach thrilled me just as much the second time, although I paused with concern to reconsider the dank little rivulet trapped behind a buildup of pebbles.

From here I could see past the pebble strip I was on to how the beach I assumed was Dixon’s curves to the point at the High School and that, in fact, this wasn’t all that far away.

There is a path you’re encouraged to take as your near the high school, but I’d come back after my beekeeping course was over, and walked that then, trying to shrug off a small despair that had nothing to do with the keeping of bees. That path sometimes uses streets, sometimes paths through bush and across grassy spaces, and sometimes brings you to cliff tops and as a result I was beginning to wonder about the geography behind the beach too.

Rather than choosing this path again I continued along the pebbles beneath tall yellow, unconsolidated cliffs before I stepped onto the beach that I’d identified as the one Sue Mount refers to as Dixons, but which, on a more recent visit, some locals spread on towels told me they simply call High School beach. They did not know it had another name.

As I walked along Dixons I kept a closer lookout for middens but the evidence I found was frail and barely present. I stopped to try and make sense of a layout of rocks that brought fish traps to mind, but if Tasmanian aborigines did not eat fish from 3700 years ago onwards – there was a dietary transition at this point (Johnson & McFarlane, 2015) – then why would they have built a trap, if that’s what it is? I must be one of many who have thought about this because on that later visit one of the people I stopped to chat with on this beach had wondered the same thing and as archaeologists have visited the midden on Dixons, they must have regarded/disregarded this feature too. It doesn’t feature in Jim Stockton’s Tasmanian Naturalist article on the matter.

I rounded the point I thought was Cartwright’s, puzzled, because it was disassociated from the reserve to which it was supposed to be attached. Instead the school grounds rise behind it. Is there a school anywhere else in Australia that has such a fantastic setting – surrounded by two beaches and a third (Retreat) across the road really just artificially divided from the other two?

There was a small cluster of seabirds hanging out on the boulders at the point (not Cartwright’s at all, but High School Point, just to be clear). There nearly always are seabirds here and, buoyed by this fabulous walk, I adjusted the pick up arrangements and then I carried on walking.

(Andrew Short’s report is referenced on The Bookshelf page).

Johnson, M & I McFarlane. 2015. Van Diemen’s Land: an aboriginal history, UNSW, Sydney