Derwent River: Rivulets: Meeting Wayne

Had I been more attuned to the landscape, I might have immediately realized that this city was criss-crossed with rivulets but it was only after leafing through a report about Wayne Rivulet back in 2003 that I began to observe the landscape more carefully (or so I thought) and recognised that if we valued natural landscapes more highly Hobart could have been an even more beautiful city.

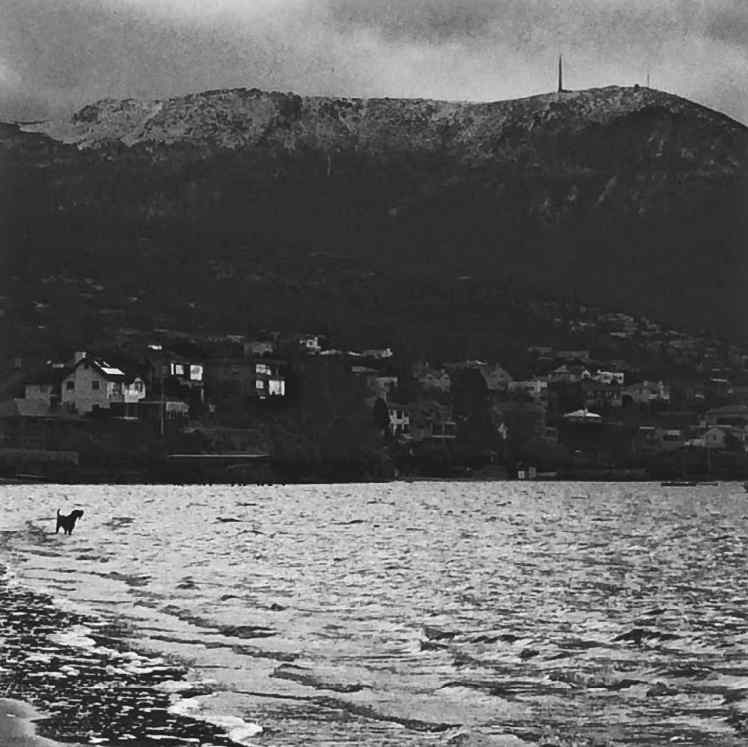

One rainy Saturday that year, the report in my hand, three of us went in search of Wayne. We drove through Sandy Bay paying attention to the dips and hollows where rivulets once might have flowed and we went to Long Beach to seek Wayne’s mouth because I’d read that according to Wooraddy – or so George Robinson said in his journal – there used to be a large Aboriginal village there. And if this was true then a rivulet would be a most necessary resource. I discussed the possibility of a village with an archaeologist I knew and he wasn’t too sure he trusted Robinson on this issue and let’s face it, a language barrier can lead to a lot of misinformation. Elsewhere in the literature it’s considered to have been a camping site.

In 2003 the beach was disappearing so fast that efforts were being made to shore it up. We stood on this little remnant of beach and figured out that the rivulet emerged where new works were happening at the southern end, and then I noticed that we’d actually parked right above the stormwater drain, which is now the mouth of Wayne Creek.

After a little exploring around the area we found the rivulet again higher up the slope at Fahan School. A sign testified to their care of the rivulet and how they used it for educative purposes but it looked crestfallen that day and damaged by diversion. It flowed over watercress and then into a more established looking bed below the willow trees and under a little wooden bridge. Its bed grew deeper and cut around the edge of a small shed, ran under the road, emerged again just briefly then disappeared completely until it reached the end of the pipe at Long Beach.

A scientist friend who knew about Wayne said it was corroding the diesel tank under the BP petrol station (now United) and so that spot is on the contaminated sites register. I asked a Fahan student if she knew where Wayne Rivulet was and she said she’d never heard of it. When I told here where she could find it, she said, ‘we just call it ‘the creek’ but after our conversation she went looking and told me about the signs in the playground. ‘So I probably did know,’ she reasoned.

We climbed up behind the school and tried to track Wayne to its source higher up Mount Nelson. We figured it had to be near a large purple house on the upper slopes but in fact, although two tributaries are said to flow into Wayne, we had no luck finding any trace of any rivulet above Churchill Avenue. There were new houses encroaching into the bush up there and they impeded our search.

It’s now 2015 and Wayne Rivulet remains largely unknown to Hobartians, but that’s also true of the other disregarded rivulets, most being unassuming, sporadic and unknown. Today I went back to take a peek at Wayne and I was disappointed to see that it looked as crestfallen as ever.

Not that long ago a friend and I did a walk from the mouth of Lambert Rivulet at the Derwent Sailing Squadron, up the shady gulley to the top of Mount Nelson and down through the Truganini Reserve to Cartwright Creek in Taroona. Lambert enjoys a lot of daylight and makes its way through a densely foliaged linear reserve. It’s the lucky one, along with a tiny handful of others.

Chatting as we walked, we wandered across the catchments of the other Sandy Bay Rivulets that these days are sealed up tight until they get to the river, but there was so little evidence of their presence that lost in conversation and good company I did not pay attention to the landscape and forgot to pay my regards to those neglected rivulets.